The Polyvagal Theory

With anxiety, depression, and stress on the climb, have you ever wondered how you could understand your reactions to life’s challenges and stressors? Or maybe you wondered how you could become more resilient? Did you know that you can map your own nervous system?

This powerful tool can help you shift the state of your nervous system to help you feel more mindful, grounded, and joyful during the day and more importantly, during your life. Before we discuss how to map your nervous system, let’s break down the autonomic nervous system a bit more.

The terms “fight or flight” and “rest and digest” are typically what we refer to when discussing this autonomic nervous system. However, there are different aspects of the nervous system referred to as the polyvagal theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges.

The vagus nerve, referred to as the wandering nerve in Latin, is one of the longest nerves and is a cranial nerve that originates in the brainstem and innervates the muscles of the throat, circulation, respiration, digestion, and elimination. The vagus nerve is the principal constituent of the parasympathetic nervous system, and 80 percent of its nerve fibres are sensory, which means the feedback is critical for the body’s homeostasis.

Pretty impressive, wouldn’t you say?

When we are in this stressed state or potentially anxious state, then we cannot be curious or be empathetic at the same time. In addition to being unable to be empathetic or curious, we are also unable to break the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for executive function, to communicate, guiding, and to coordinate the functions of the different parts of the brain, back online. This means that we cannot regulate our attention and focus. Sound familiar?

Three Nervous System States

First, our “fight and flight” response is our survival strategy, a response from the sympathetic nervous system. If you were going to run from a tiger, for example, you want this response to save your life. We can have anger, rage, irritation, and frustration when we have a fight response. If we have a flight response, we can have anxiety, worry, fear, and panic. Physiologically, our blood pressure, heart rate, and adrenaline increase, decreasing digestion, pain threshold, and immune responses.

Second, we have a “freeze” state, our dorsal vagal state, which is our most primitive pattern and is also referred to as our emergency state. This means that we are entirely shut down. We can feel hopeless and feel like there’s no way out. We tend to feel depressed, conserve energy, dissociate, feel overwhelmed, and feel like we can’t move forward. Physiologically, our fuel storage and insulin activity increases and our pain thresholds increase.

Lastly, our “rest and digest” is a response of the parasympathetic system, also known as a ventral vagal state. It is our state of safety and homeostasis. If we are in our ventral vagal state, we are grounded, mindful, joyful, curious, empathetic, and compassionate. This is the state of social engagement, where we are connected to ourselves and the world. Physiologically, digestion, resistance to infection, circulation, immune responses, and our ability to connect are improved.

We humans have and will continue to experience all of these states. We may be in a positive, mindful condition and all of a sudden, due to a trigger, be in a frustrated, possibly angry state, worried about what may happen, then feeling completely shut down. This is the human experience. We are going to shift through the states naturally. However, when we stay in this fight or flight or shut down/freeze state, we begin to have significant physiological and mental/emotional effects.

As I mentioned earlier, this could be an emergency state. This can also be a suicidal state if we are in this shutdown mode for too long. If we are in a fight or flight state, we can constantly activate our stress pathway, also known as the HPA axis, and we can really impact our stress hormones, sex hormones, thyroid, etc.

This stress will have significant inflammation effects on the body as well. All these states can have a considerable effect on our overall health, positive or negative. Also, you can not get well if you are not in your “safe” state. No treatment intervention or professional will help you if you are not safe. This is why it’s important to identify the states for each of you.

How can you map your nervous system?

1. Identify each state for you.

The first step is to think of one word that defines each one of these states for you. For example, if you are in your ventral vagal state, also called the rest and digest state, you could say that you feel happy, content, and joyful. Etc.

When you are in your fight or flight state you could use the words worried, stressed, overwhelmed, etc.

In the freeze state, you could use the words shut down, numb, hopeless, etc.

The first step is identifying the word that you correlate with each of those three states. This is important because then you can recognise which state you are in and identify with it quickly. This will allow you to tune in to your body and understand how you feel in that state, so you can help yourself get out of it.

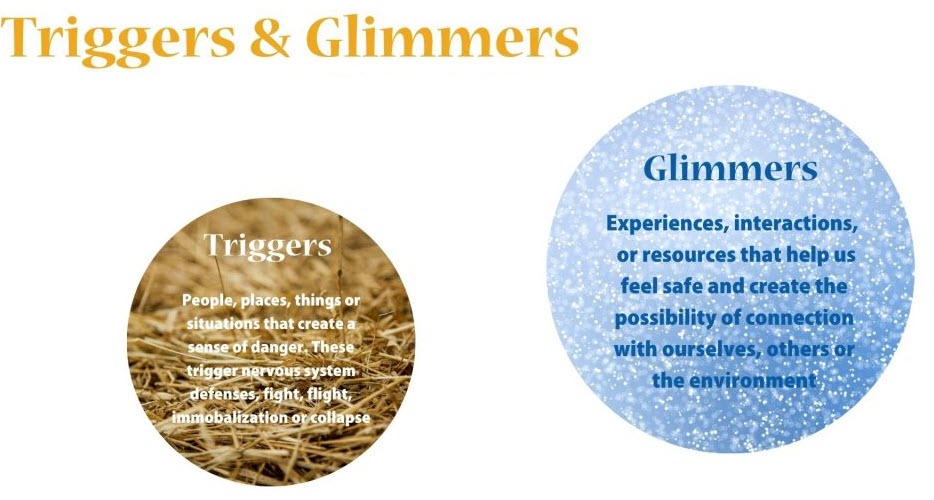

2. Identify your triggers and glimmers.

You’ll want to identify triggers for your fight/flight state as well as your freeze state. These could be things like a fight with your boss, an argument with your spouse, the death of a loved one, if someone cuts you off while driving, etc. It is whatever things that cause you to feel stressed. You want to eventually have at least one trigger, if not many, written down for each of those states.

Glimmers are the things that bring you to that optimal nervous system state. It could be something as simple as petting a dog or something bigger like going on a vacation.

Summary

Once you can identify what those states are for you, you can recognise your triggers and glimmers for that state. You can begin to make a profound difference in your nervous system state. You can take ownership of what’s happening to your body, tune in to what’s happening, and know how to regulate your emotions and your responses to stress.

Ultimately, this is how we can begin to develop resilience. This means being able to have responded appropriately to life’s challenges, go to that fight or flight state for a short period, and then return back to your state of social engagement. That should happen a few times a year, not multiple times a day, or every day. To truly enjoy life, returning to your state of safety, where you are mindful, grounded, and joyful, is a practice. It can start with mapping your own nervous system.

If you need help on your journey, please reach out!